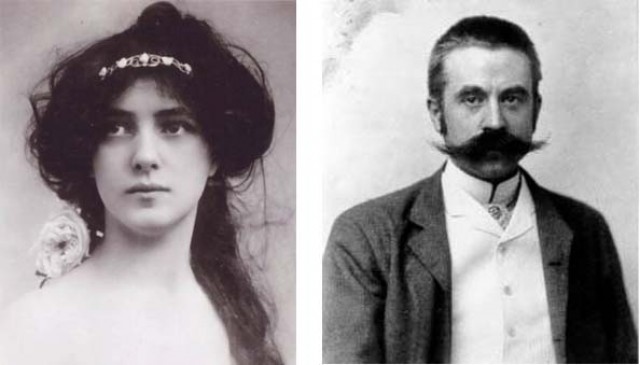

Evelyn Nesbit was the teenager that defined modern beauty at the turn of the century and spent her teen years socializing like a starlet with the greatest patrons of the arts. That is until she became embroiled in “the crime of the century,” which would define her adulthood. Evelyn was a teen in a time that, like ours, valued youth and the ability to make free-flowing clothes look gorgeous, and in which teenagers passed as adults in all but experience.

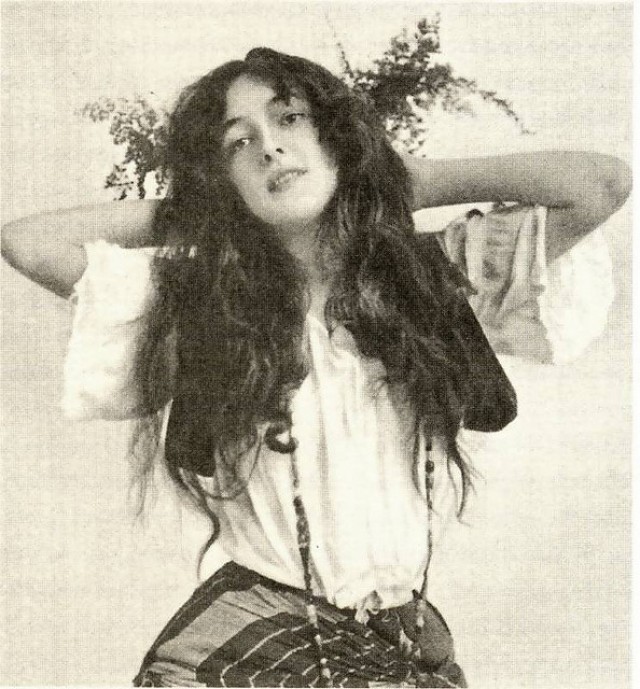

Growing up poor outside of Pittsburg, Evelyn was able, thanks to her stunning beauty, to find work as an artist’s model during her early teen years. At fifteen, she moved with her mother to a tiny room in New York City, having learned that fashion photography was becoming a lucrative possibility for young models. Evelyn posed for photographers dying to capture her mass of dark hair, narrow shoulders, and diminutive figure, which never required a corset. Her uniquely modern look, which combined unconstrained exoticism with youthful innocence, made her the perfect muse. Her face is said to have inspired the image of the famous Gibson Girl, the symbol of the feminine ideal.

Nesbit was sixteen when she became a chorus girl in a show called “Florodora Girls” and her small part as the gypsy maiden caught the eye of New York’s most famous architect, Stanford White. A notorious admirer of feminine beauty, White attended that particular show on a nightly basis. Parties would follow the show at Rector’s on Forty-third street, a nightclub popular with the theater crowd, which was nicknamed “the cathedral of froth.” The considerably younger Evelyn, who had kept her age quiet to get the role, never drank more than a splash of champagne thanks to her mother’s warning that alcohol would spoil her looks. For months, she participated in innocent if enthusiastic socializing with the theater crowd and their patrons, attending splendid parties at The Madison Square Garden rooftop, Tiffany’s, Sherry’s, and Delmonico’s.

When Stanford White invited her to lunch at his private house on 24th Street, she was permitted to attend only in the company of some older girls. White toured her around his discreet pied-a-terre and, in an anecdote that would become legendary, invited her to play on his red velvet swing while he watched in a state of aesthetic ecstasy. The two became fast friends, with the forty-five year old White acting as a mentor and benefactor to the pretty teenager. White would suggest books for her education and she was worshipful of his opinions and intellect. He also introduced her to famous photographers, for whom she often posed nude and played out fanciful, artistic visions. Eventually, the famously charismatic architect managed to charm Evelyn’s mother into placing her in his care whenever she went away.

At a time when muckraking journalism was in its heyday and papers hungered for scandal, it seems miraculous that the media continued to portray White’s relationship with Evelyn as avuncular in nature. In fact, Stanford White took advantage of Evelyn, who thanks to the same youth and innocence that made her poses so alluring, never suspected his intentions until it was “too late.” After losing her virginity to White in a room in his 24th Street apartment that was covered in floor-to-ceiling mirrors, she would forever consider herself a “ruined woman.” She had to refuse the engagement of a 19-year old aspiring cartoonist whom she dated. Acting as her benefactor, White officially disapproved of her relationship with the cartoonist and advised her mother to forbid it. She was sent to boarding school in New Jersey to ensure the separation.

Evelyn’s affair with White ended before she turned 18, and the next man who would propose to her was the certifiably insane young millionaire, Harry K. Thaw, whom she married apparently out of fear, and a sense of obligation. Over the course of their short marriage, Thaw would force Evelyn to recount the story of her de-flowering at will and refer to White as “the beast” in his presence. Thaw also forbade her from stepping foot in any buildings of Stanford White, who was, incidentally, one of New York history’s most prolific architects; the ban included many of Evelyn’s old haunts, like Tiffany’s, Madison Square Garden, and Sherry’s, to name a few.

When Evelyn was 21, the couple inevitably broke Thaw’s own rules and attended a performance at Madison Square Garden, where they promptly ran into White. Thaw had been carrying a pistol in case of the event. At the after-party, Thaw shot and killed White in front of hundreds of witnesses, many of whom swore Thaw shouted “you ruined my wife” as he delivered the fatal shot, while just as many others insisted the word had been “life.” In what became known as “the trial of the century,” Thaw was declared not guilty by reason of insanity.

The media maelstrom surrounding the trial depicted Evelyn as a victim of Stanford White’s moral decay, which defense lawyers pointed out was evident in his decadent architecture. Though she moved on to a divorce, and a career as a dancer in Europe, thanks to the trial, history remembers Evelyn as her teenage self, a young woman in childlike enthrallment of visual splendor and a fabulous social life. Her first relationship may bear the characteristic brevity of teenage love, the stamp of Nesbit and White’s shared tastes lasts in visual culture. Their story invites us to read adolescent exuberance, and even its self-consciousness, into flowing clothes, up-swept hair, and sensuous architectural details.

images via flickr

►Walk it out. Learn more about Evelyn Nesbit and her haunts at

Travelgoat – Evelyn Nesbit Teenage Starlet Tour

—Zach Aarons was born and raised in New York City. He currently lives in Fort Greene, Brooklyn and serves as a tour guide, urban historian, and travel guru. Zach is the CEO of Travelgoat, an online urban exploration guide. He is interested in utilizing technology to make touring and exploration more fun, efficient, and reasonably priced. As a teenager, Zach was devoted to playing football and the French Horn.

—Artie Niederhoffer lives in New York where she continues to enjoy many of her favorite teenage pastimes. She regularly hangs out on street corners, paints her nails, makes collages from magazine clippings, and generally tails youth culture. Her writing about urban history and culture appears in Travelgoat, The Faster Times, The Cipher, and several personal blogs.